| Erebuni Museum |

|

| ||

| Section

6

6A. Oak Wood Fragments. 3000 years old, these fragments of oak were used for columns, door and window casings and roof construction. Roofs at Erebuni were made by crossing wood beams and covering with woven reed mats. The wood has been compared with those found at other sites in the Ararat Valley hat, along with geographical studies of the region show that as late as the Urartu Empire the valley held vast stands of forest.

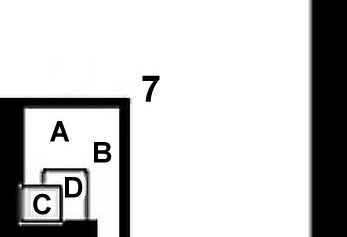

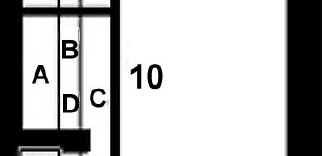

Section 7 7A. Iron pipes (fragments, ca. 200 BC) used for drainage and bringing water into the citadel. The piping system illustrate a predilection for hygienee not common in the era. 7B. Bronze Door Lock is among the bronze and iron items in the display. 7C. Bronze Vessel 7D.

Molds used for pouring iron and bronze.

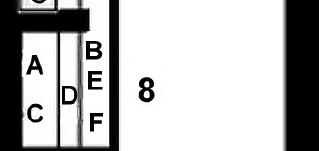

Section 8 8A. Weapon Fragments include Arrow Heads, Quivers and breastplate Fragments. 8B. Weaponry include helmets, spear, small sword and word fragments, slings, arrows. 8C. Stone Vessel. 8D. Stone Ax Head. 8E. Poultice Stone for grinding paint pigments. 8F.

Polishing and Grinding Stones used for sharpening and polishing weapons

and metal or stone items.

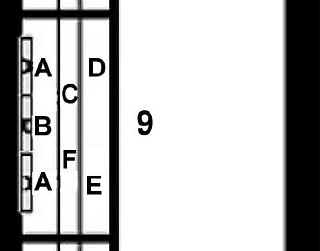

Section 9 9A. Drawing of Erebuni 9B. Drawing of King's raiment 9C. Fragments of Urartian clothing and Sewing Artifacts include fragments from aristocratic household, needles, thread spinner and pieces from a loom. 9D. Ceramic Oil lamps, divided into two halves, the smaller well linked to the larger by holes. The wick sat in the smaller section. 9E. Pottery Wheel 9F.

Stone Wings from an Idol.

Section 10 10A. (inside drawer) Vessel Fragments include handles and two-handled pieces. 10B. (upper case) Small ceramic bottles used for holding medicine, perfume and ointments. 10C. (small case towards end) Funerary jar where ashes of the deceased were placed. Note the three holes. They were cut so that the soul of the deceased could leave the confines of the jar. 10D.

Large

Storage Jars. The corner jar is decorated with designs representing

water and wheat, also found at Metsamor jars dating to 4500-4000 BC.

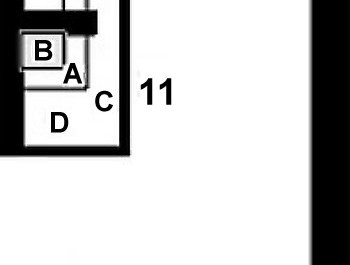

Section 11 Artifacts from an Urartian Tomb One of the most important displays in the museum are these artifacts uncovered in 1984 by Armenian archeologists (see side piece). 11A. Ceramic Vessel. This vessel is adorned with concave lines and sculpted heads of bulls. Vessels of this type were of common occurrence in the empire, and is a replica of respective bronze vessels widespread in the area. 11B. Ceramic Vessel. The vessel is adorned with three belts and a statuette of a lion, reminiscent of that uncovered at Teishebaini (Karmir Blur) and a symbol of Yerevan. 11C. Stamp. The black stone seal depicting a griffin holding a snake in its beak. Scenes of fighting birds and snakes are thought to depict the concept of the Universe's eternal struggle between good and evil, current in Urartian mythology. Four types of seals have been uncovered in Urartian excavations: cylindrical, bell-shaped, animal-shaped figurines and weight-shaped, as in this example. 11D. Agate and Quivers. The collection includes 28 finely polished and drilled, 12 bell-shaped agate beads and 3 disk-shaped bead partitions; a bronze pin adorned with a bas relief of of four ram heads; large bracelets decorated with the heads of snakes (broken into pieces and twisted before being placed into the grave). The bronze quivers are unusual for the region, shaped as tubes with two rings affixed to each. The remains of a wooden bow are the bronze bow ends on display. |

| |

|

| ||

|

The

Baini Tombs in Yerevan

One of the more important finds in Armenian archeology occurred like so many others around the world--by accident. When construction of a new factory was begun in 1984, a large graveyard was uncovered. Further excavation by archeologists from the Armenian Academy of Sciences uncovered a sepulcher in the graveyard from the Urartian period, stone-coffins from the Early Bronze and barrows from the Middle Bronze Ages. Pottery from the early 1st millennium BC was found adjacent to the old graveyard. The 8th century BC sepulcher is floored with polished black, red and dark-brown tuf stone slabs, with caches underneath. The walls were built in five layers, of finely crafted tuf, with five niches, three of which were fitted into the western wall, each containing an urn filled with fragmented bones of humans, animals and birds. A niche of the same size was fitted into the southern wall. On the eastern wall a longer niche was found, spanned by a large tuf beam which supported most of the weight of the stone slatted roof. The niche held a large clay vessel decorated with the heads of three bulls, in addition to a bowl with a rabbit-effigy stamp on the base. Five large tuff beams span the upper walls from east to west, with another two completing the roof construction running from north to south. The entrance to the sepulcher lies on the northern side, hermetically sealed with a massive tuf stone. Artifacts in profusion were found in the tomb, including a pitcher with a lion-headed spout, an ewer, a lamp holder and a number of bowls at the northeastern corner. Underneath the floor slabs at the western end of the tomb, three caches were found, one holding bronze quivers, a bowl, agate beads, a weight-shaped seal of black stone engraved with the effigies of a griffin and a crescent. The second cache held bracelets with snake heads. The third cache held remnants of three different straps and saddles, snake-headed bracelets, an iron sharp sword, knife and daggers, bronze nails, a bucket and other artifacts. The high quality pottery is in two types: wide-mouthed, slender-bodied with wide base vessels, high necks and protruding lips and those wrought with animal figurines. The first were bored with three triangular holes on their sides. Similar urns have been uncovered at other excavations in Armenia. The second group of pottery comprised two vessels wrought with animal-shaped figurines, one of which was adorned with three belts and a statuette of a lion, reminiscent of that uncovered at Teishebaini (Karmir Blur) and a symbol of Yerevan. The second vessel is adorned with concave lines and sculpted heads of bulls. Weaponry uncovered included a 0.90 cm long iron sword, three daggers are in the style popular in the Near East and made in Armenia in Middle Bronze Age up to the 8th century BC. Three leaf-shaped spear heads and two almond-shaped arrowheads were also found. The horse saddles included harnesses, head stalls, bells, buckles and a number of curb chains. The headstalls are of bronze. Far from the confines of Erebuni, the graveyard is thought to have been used for a separate city, and may have been the beginnings of present-day Nor Aresh. Further excavations are hoped to reveal the existence of a third habitation within the limits of Yerevan (Erebuni and Teishebaini or Karmir Blur being the other two) at the time. Urartian monuments have also been uncovered in the residential areas of Charbakh, Noragavit and Toumanian Street, all in Yerevan. This suggests a much larger area of human occupation. Burial and Religious Beliefs The tomb, like others found in Armenia and Anatolia, shows a pattern of belief in the soul and after-life. It further elaborates a system that revolves around birth-life-death-afterlife, with the "dwelling" of the soul making up the most significant element of burial. It is believed that the Urartian god Adaruta was the symbol of birth, Irmushini stood for disease, life and health, while the emblem of death was represented by a deity that "transferred the souls". By believing in a deity that "transferred the souls", Urartians showed a distinct belief system, regardless of other traditions and cultural effects they adopted. They had their own legends concerning the soul, the other world, the boundaries between this and the the other worlds, and that the soul alone could not cope with the incumbent problems of that existence. Apparently the soul met with another god on the borderline of the other world--Shebitu, who like his Mesopotamian counterpart Sabitu-Siduri, guarded the entrance. The idea of the other world was related to the concept of water--the ocean or sea--an example of which was Lake Van, a reason for their occupying the adjacent area for their capital. As with ancestral Armenian beliefs, life in the other world was similar to that in this world, except for the fact that it was reversed as in a mirror. Instead of the human, it was the soul that was in need of food, clothing, arms, implements and means of travel in the other world. Khutuini, the fourth deity in the pantheon as master of humankind's destiny, was supreme ruler of the other world. The idea that the road leading to the other world must have passed through caves and grottoes, as well as "gates", is testified to in burial forms found in rock openings or manmade caves. Significantly, If the deceased was buried in the ground, the latter was covered with a stone "shield" with a central "gate" at one end. it was believed that the gods emerged from the rocks to maintain contact with humans, and there was a habit of dedicating the "gate" to one god or another (usually Khaldi, the supreme deity over all others). Despite a unifying concept of the other world, individual burial rites are markedly dissimilar, reflecting the geographic and prevailing ethnic make-up of individual regions. Three basic types of burial have been uncovered: burial of an intact body, cremation and dismemberment. Burial of the Body Intact: This rite--practiced throughout the Armenian Plateau in all stages of development--varied in Urartu with the corpse buried in caves; in a sarcophagus placed within a subterranean, single-or-multiple-sectioned cell made from stone, with dromos; in a rock opening, stone coffin, large stone-walled grave, earthen vessel or directly in the ground. Cremation: Originating in the Armenian Plateau in the Bronze Age, the rite of cremation persisted until the adoption of Christianity, and varied by laying the vessel containing the ashes of the corpse in a rock opening, a man-made cave, in a stone coffin, in a burial cell with dromos, or directly in the ground. Dismemberment: Also originating in the Armenian Plateau in the Bronze Age, this rite persisted until the early Middle Ages AD. In its earliest practices, it consisted of removing certain bones from the skeleton or by dismembering the skeleton when the bones were not collected in urns. In Urartu they were invariably placed into urns with opening bored into the sides (of the urns). Variations of burial included placing the urn into a stone coffin, buried in the ground or places in a wall niche of a stone burial cell with dromos. Despite these variations, widespread use of all two are all three types of burial can be found in within the same graveyard, suggesting the empire policies of the Urartians promoted movement of tribes with differing traditions throughout the region. Especially in the reign of Argishti I, migration within the empire was encouraged as a way to promote central administration and control, much as the Romans did 500 years later to solidify their territorial gains. Some have suggested this shows the hydrogenous nature of the ethnic groups in the Armenian Plateau, while others believe the general principles surrounding all burials and the belief in the other world and its passage shows a deeper homogenous Indo-European character among all tribes with dialectical differences, and some integration of Hurrian, Alarodians and surrounding cultures. The graves at Nor Arash and Erebuni show the variety of Indo-European and neighboring cultures predominate in the area in the 8th century BC, many of whom were resettled during the reign of Argishti I (280,000 settlers) and Sardur I (197,000 settlers). The resettlement had a profound affect on the local culture, which had been separated from the west after the fall of the Metsamor Kingdom (date unknown), and during the Nairi confederation. Artifacts and burial rites uncovered from the earlier period show a striking similarity to that found in the western Armenian Plateau, showing a much earlier and closer tie within the entire area as early as 5000 BC. | ||

| Section

12

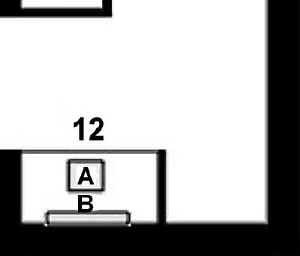

12A. Stone Carving of an unknown god. This piece is simple in design and possibly dates to the early or middle Bronze Age. It is evocative through its full-face depiction, the first known frontal depiction of a god, which were rigorously shown in profile. 12B. Picture of 4 Stone Idols found in the excavation. |

| |