As

early as the reign of the Assyrian king Shalmanaser I (1280-1266 BC),

mention of Urartu is made, under the name "Uruatri". Shalmanaser’s texts

describe a campaign against 8 countries collectively called the Uruatri.

The size of the country is not described, but it is likely other tribes living in the area around Van were included in the alliance, since the Assyrian name Uruatri had no ethnic significance but was probably a descriptive term (perhaps meaning "the mountainous country"), since reference to the Nairi is still made In texts written in the name of Shalmanaser I’s son, King Tukulti-Ninutra I.

In the 11th c. BC Assyrian annals return to the name Uruatri or Uruartu, while in others both Uruatri and Nairi are used interchangeably. Dominant tribes were absorbing city-states, forming more than an alliance, they were becoming a large kingdom, and through the Urartians, an empire.

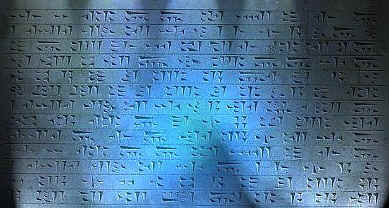

By the 11th c BC, the Nairi tribe had fallen, and Assyrian tablets from this period make the first mention of "Urartu" as a strong power. Also at this time Assyria went into 200 years of decline, allowing Urartu to develop and expand its influence. Hurrian influences continued, but the Urartu tribe began to absorb Assyrian culture, including the use of cuneiform to replace pictogram writing. By the 9th c. BC the Urartu kingdom had established its regional power far beyond its capital at Tushpa (present day Van), invading Mesopotamia, and unifying the tribes in the Armenian plateau into one centralized state. The Urartians consistently cut Assyria from the trade routes to the Mediterranean, and enjoyed a monopoly on commerce between Asia and the West. The Urartians called their country Biainili (the name "Urartu" comes from the Assyrian language).

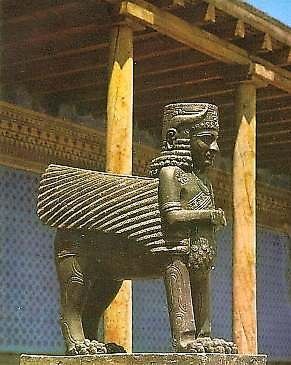

Urartu was a remarkably developed culture that had extensive contacts with the major empires of the Ancient world stretching between the Mediterranean and India, and rivaled them for trade, military and cultural hegemony. Urartian timber was shipped to Egypt, its metal forges were used to produce iron weapons and tools, and its development of irrigation created vast agricultural tracts. They worshipped a pantheon of gods which closely resembled those in other empires, and their temple architecture show a similarity to that discovered in Ur (ca. 3500-2000 BC) and Babylon. It is known that when the Assyrian king Shargun II built Dur-Sharukin, he incorporated details from Urartian secular design schemes into his throne room. Frescoes found in the excavation of Erebuni in Yerevan are virtually identical to those later used by the Assyrians.

The

Urartians had a centralized government, led by a king successfully binding

a federation of tribes into a large empire. Often at odds with

the Assyrians, their history parallels the rise and fall of the Babylonian

and Assyrian empires, but at their height in the 8th c BC, they capture entire

Assyrian provinces, invaded Babylon, going as far as the river Diala, and

usurped Assyria's trade routes. exacting tremendous tribute to allow passage.

The

Urartians had a centralized government, led by a king successfully binding

a federation of tribes into a large empire. Often at odds with

the Assyrians, their history parallels the rise and fall of the Babylonian

and Assyrian empires, but at their height in the 8th c BC, they capture entire

Assyrian provinces, invaded Babylon, going as far as the river Diala, and

usurped Assyria's trade routes. exacting tremendous tribute to allow passage.

One the earliest of the Urartu kings was Ishpuinis (Ispuinis), who was so successful in his campaigns against the Assyrians he began to assume titles of ever-increasing pomposity and glory. From "Ruler of Tushpa", he soon added the titles, "King of the Land of Nairi", "Great King", Powerful King" and King of the Universe". Ishpuinis succeeded in stretching the empire close to the edge of present day Armenia, along the Arax River, but was repelled by local tribes. Contemporary accounts show a series of attacks and counter-attacks between the Urartians and local kingdoms. At the same time, they were repelling repeated Assyrian attacks, and had so grown in wealth and military importance, that other tribes in the now "Nairi-Urartu" federation began to organize their own attacks against the new empire.

The first wave of outright war between the two great powers occurred during the reign of the Assyrian king Shalmanaser III (860-825 BC), who had reformed the Assyrian empire and brought it out of decline. Shalmanaser III achieved success in the first three years of his reign, profusely recorded on bronze gates uncovered at the Assyrian city of Imgur-Emil southeast of Ninevah. The bronze gates record Shalmanaser III’s continual wars with the Urartians, glorifying in detail his control over an "unruly tribe". The bronze gates can be considered an early form of "billboard advertising" since they were hung where all could see them, and were "updated" with bronze impressions after each Assyrian campaign.

Campaigns against the Urartu king Aramu destroyed several Urartian cities, but the Assyrians never succeeded in reaching the heart of the kingdom, and successive campaigns focussed more and more on peripheral areas of the country. By the end of Shalmanaser III’s reign, the bronze gates record no victories and hint at defeat at the hands of a new Urartu king, Siduri (Sarduri). Sarduri was so confident in his power he had a erected massive wall at Tushpa, where inscriptions were carved in Assyrian and Urartian giving himself the titles "the magnificent king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of the land of Nairi, a king having none equal to him, a shepherd to be wondered at, fearing no battle, a king who humbled those who would not submit to his authority." No problem with self-esteem there.

Menuas, Argishti and Sardur I

The

real rise of the empire of Urartu is centered around three kings: Menuas,

Argishti and Sardur I. Menuas in particular established the outlines

of the empire, and organized the centralized administrative structure that

enabled his son Argishti and grandson Sardur II to extend the empire to its

furthest reaches. During his reign Menuas reached the northern spurs

of Mount Ararat and reached the banks of the Arax River. He established

a stronghold named Menuakhnili (starting an Urartian tradition of naming cities

after kings) in the environs of the present day village Tashburun. Menuas

spent much of his efforts in internal organization of the empire, and most

likely because of this Assyrian cuneiform do mention him. Urartian cuneiform

shows that Menuas fortified the citadel of Tushpa and established cities and

strongholds throughout the empire. The fortified cities he had

built were placed so that communications between even the farthest reaches

of the empire and Tushpa could raise an invasion force within a matter of

hours. Of particular note, Menuas developed extensive irrigation within

the Urartian Empire, some of which are still operating. Of these, the

mistakenly called Shamiram (or Semiramis) canal was built during the reign

of Menuas, and still supplies water to the region of Van.

The

real rise of the empire of Urartu is centered around three kings: Menuas,

Argishti and Sardur I. Menuas in particular established the outlines

of the empire, and organized the centralized administrative structure that

enabled his son Argishti and grandson Sardur II to extend the empire to its

furthest reaches. During his reign Menuas reached the northern spurs

of Mount Ararat and reached the banks of the Arax River. He established

a stronghold named Menuakhnili (starting an Urartian tradition of naming cities

after kings) in the environs of the present day village Tashburun. Menuas

spent much of his efforts in internal organization of the empire, and most

likely because of this Assyrian cuneiform do mention him. Urartian cuneiform

shows that Menuas fortified the citadel of Tushpa and established cities and

strongholds throughout the empire. The fortified cities he had

built were placed so that communications between even the farthest reaches

of the empire and Tushpa could raise an invasion force within a matter of

hours. Of particular note, Menuas developed extensive irrigation within

the Urartian Empire, some of which are still operating. Of these, the

mistakenly called Shamiram (or Semiramis) canal was built during the reign

of Menuas, and still supplies water to the region of Van.

The wars between Urartu and Assyria accelerated during the early years of the reign of Argishti I. Though Menuas had an older son, Inushpuah, he did not succeed to the throne. Historians believe he became head priest of Khaldi (the chief god in the Urartian pantheon) at Musasir, which was the religious center for the country. Argishti, Menuas' younger son, succeeded to the throne in 786 BC, and was immediately embroiled in war with a newly revived Assyria, which suddenly began to expand its empire, and had particular eyes on the rich mining resources in the Armenian Plateau.

The attacks against Urartu were a tactical error. Allowing Assyrians to cross the border on the Southern side, Argishti quickly consolidated early gains made against the invading army by outflanking the Assyrians in their provinces, through which her trade routes stretched. Pursuing Assyria on the south and east, his army conquered the countries of Melitanuh and Komaguenuh and invaded Babylon itself (by this time a possession of the Assyrians), reaching as far as the river Diala. Argishti succeeded in checking Assyria’s northern expansion for 50 years. One of the greatest generals at the time, the Assyrian Turtan Shamsheluh faced his only defeats by the Urartians. An inscription found at Tel-Borsippa shows a frustrated Shamsheluh frankly admitting who was the better general: "(Argishti)…whose name is as terrible as a dreadful storm, whose might is immeasurable, who cannot be compared with any one of the previous kings…"

Taking advantage of the fulcrum Menuas established at Menuakhnili, Argishti I crossed the Arax River and penetrated the Ararat Plain. He and his son, Sardur I expanded the empire as far as both shores of Lake Sevan, up to the edges of modern Georgia, incorporating most of the territory of the current Republic into its reaches. He ordered the building of several key outposts, among them Erebuni in 782 BC, which is considered the beginning of Yerevan’s history, and Argishitinili (present day Armavir).

Erebuni

was established in the foothill area on the edge of the Ararat Valley and

served as a base for the Urartian advance into the area around Lake Sevan,

a mountainous region rich with cattle, occupied by tribes with Hurrian roots.

The citadel of Erebuni contained a royal palace, a temple and storerooms.

In the year before, campaigns in Northern Syria conquered the kingdoms of

Hatti and Melita, and 6,600 prisoners captured in those wars were forced to

build and settle the new city at Erebuni. Tablets at Erebuni proclaimed

Argishti’s power, building a city "to declare the might of the land of

Biaini and hold her enemies in awe".

Erebuni

was established in the foothill area on the edge of the Ararat Valley and

served as a base for the Urartian advance into the area around Lake Sevan,

a mountainous region rich with cattle, occupied by tribes with Hurrian roots.

The citadel of Erebuni contained a royal palace, a temple and storerooms.

In the year before, campaigns in Northern Syria conquered the kingdoms of

Hatti and Melita, and 6,600 prisoners captured in those wars were forced to

build and settle the new city at Erebuni. Tablets at Erebuni proclaimed

Argishti’s power, building a city "to declare the might of the land of

Biaini and hold her enemies in awe".

Six year’s later Argishti established a new city in the Ararat Valley on the ruins of Armavir, calling it Argishitinili ("built by Argishti"). The city boasted cyclopic walls reinforced by towers, within which were temples, storerooms, and in the citadel, a new palace. Inscriptions found at the site bear witness to the importance of the city as an administrative and religious center, while Erebuni was used primarily as a military fortress.

By the end of Argishti I’s reign, in the middle of the 8th c. BC, Urartu was at the zenith of its power. It’s authority stretched between the Transcaucasus, Lake Urmia in present-day Iran, and well into the Hittite territory in the west. Northern Syria was dependent on Urartu, which now controlled the main trade routes to western Asia. Urartu barred Assyrian expansion into Asia Minor, and its culture had begun to penetrate into the Mediterranean area and the interior of Asia Minor. Urartian artifacts and design were used not only on mainland Greece but also as far away as Italy.